Advertisement in Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung.1

As the surge of the Monopolfilm in Germany began at the end of the year 1910 it transformed the way cinemagoers perceived films. A transition from a program based approach to a centric one pivoting around feature films took place and alongside promotional practices changed with it. While it was common practice for a production company to accompany a release with posters the aspect of promotion evolved over the months as well.

About a year later it was increasingly common for local producers and distributors to accompany the releases of their films with extensive promotional material. Among other possibilities they provided the cinema owners with items such as posters, images, photographies, booklets, printing plates (for use in newspaper ads), sheet music and even gramophone records.2 It was typically commissioned directly by the producer or national distributor themselves as they offered those directly alongside the films to the cinemas.

While some promotional material was intended for cinemas to attract visitors on-site for example through posters and stills other material was intended for pure off-site promotion. The most common form of off-site promotion were newspapers ads. Those ads could be enhanced with special printing plates. Common were film related images like portraits of actors. These plates were occasionally offered by the distributors alongside the films.

Various ads with film related printing plates in newspapers from 1911 to 1912.3

In addition to those two categories and somehow as a bridge between them there was ephemera. Ephemera in the context of cinema could have been a ticket for the visit kept as a memento but on the other hand something directly intended as give-away for cinemagoers. The sale of film descriptions in form of booklets was a common method for cinemas in that sense. They even promoted this practice with their regular advertisements.4 Occasionally cinemas commissioned those programs on their own 5 which was not always well regarded by critics.

Die Fortschritte des Kinos werden auf der soeben in Berlin eröffneten Kino-Ausstellung umfassend gezeigt. Allerdings offenbart sich in den Anpreisungen der Kinematographentheater oft ein geradezu kindliche Unkenntnis der Dinge, gegen die energisch angekämpft werden sollte. Nicht nur, daß es auf den erläuternden Filmtexten von Schreibfehlern geradezu wimmelt, es werden auf Tatsachen auf den Kopf gestellt, welche man allerdings nicht als „Fortschritte“ bezeichnen kann.6

The writer of the newspaper article referenced an exhibition about cinemas which took place in 1912 in Berlin. It was intended to emphasise the cinema‘s technological progress. Acknowledging that, he instead complains about the bad spelling and the non-factual content of the cinema‘s programs. Common behaviour which from his point of view had to be swiftly abolished.

emergence

Advertisement in Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung.7

In 1913 booklets under the brand Kino-Bibliothek appeared at cinemas via an uncommon origin. Instead of a producer or distributor in this case an independent publisher, under the name Filmtext-Verlag (in this article abbreviated as FTV), organised and produced the booklets and offered them directly to cinemas.

The FTV was founded in February 1913 by Friedrich Carl Rentsch, Willi Böcker and Rudolf Falk to produce and distribute film related synopsises and programs according to the public notice issued in the Deutschen Reichsanzeiger and consequently quoted by newspapers.8

No. 11727. Filmtextverlag Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung. Sitz: Berlin. Gegenstand des Unternehmens: Die Herstellung und der Vertrieb von Filmbeschreibungen, Filmprogrammen und ähnlichen Verlagsunternehmen, insbesondere aber der Weiterführung des von Herrn Rentsch unter der Bezeichnung Kino – Bibliothek betriebenen Unternehmens unter gleichem Titel. Das Stammkapital beträgt 20 000 M. Geschäftsführer: Verlagsbuchhändler Friedrich Carl Rentsch in Berlin. Chefredakteur Willi Böcker in Berlin – Friedenau. Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung. Der Gesellschaftsvertrag ist am 3. Februar 1913 abgeschlossen. Soweit zwei Geschäftsführer bestellt sind, ist jeder Geschäftsführer allein zu vertreten. Als nicht eingetragen wird veröffentlicht: Der Gesellschafter Rentsch bringt in Anrechnung auf seine Stammeinlage in die Gesellschaft das von ihm unter der Bezeichnung „Kino-Bibliothek“ bisher in Berlin betriebene Geschäft mit allen Vorräten und Aussenständen unter gleichzeitiger Uebernahme der vorhandenen Passiven durch die Filmtextverlag Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung ein und erklärt, dass a. der Gesamtbetrag dieser Passiven nicht mehr als 800 M ausmacht, während die Höhe dieser Aussenstände, für die er der Gesellschaft gegenüber hiermit die Bürgschaft übernimmt, mindestens 600 M betrage; b. noch realisierbare Bestände an Büchern etc. vorhanden sind, die die Differenz dieser Aktiva und Passiva ausgleichen. Herr Rentsch überlässt ferner ebenfalls in Anrechnung auf seine Stammeinlage für die Dauer des Bestehens der Gesellschaft dieser die Ausbeutung der bisher von ihm mit Schriftstellern geschlossenen Verlagsverträge, insoweit sie die Kino-Bibliothek betreffen, unter Uebernahme der in diesen Verträgen übernommenen Verpflichtungen, insoweit sie die Kino-Bibliothek betreffen, seitens der Gesellschaft Filmtextverlag Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung. Der Wert dieser Sacheinlage des Herrn Rentsch wird auf 5000 M festgesetzt, den Rest von 5000 M seiner Einlage von 10 000 M zahlt er bar ein. Die Stammeinlage des Herrn Rentsch ist damit erfüllt. Der Gesellschafter Rudolf Falk bringt in Anrechnung auf seine Stammeinlage diejenigen Rechte in die Gesellschaft ein, die er an den bei der Firma Richard Falk gedruckten Filmtexten vertragsmässig oder in der der Firma Richard Falk üblichen Weise zustehenden Verlagsrechten hat. Als Verlagsobjekte der Firma Richard Falk zu Berlin und des Herrn Rudolf Falk sind beim Mangel positiver Verträge alle die Filmtextungen anzusehen, die von der Firma Richard Falk an andere Personen oder Firmen als diejenigen, von denen die betreffenden Betextungen ursprünglich in Auftrag gegen wurden, geliefert werden. Der Wert dieser Sacheinlage des Herrn Falk wird auf 5000 M festgesetzt. Der Gesellschafter Willi Böcker bringt in Anrechnung auf seine Stammeinlage folgende Rechte in die Gesellschaft ein: Alle Verlagsrechte, die ihm und der von ihm geleiteten „Erste Internationale Filmzeitung“ zu Berlin von Filmfabriken, von deren Filialen und von Filmherausgebern in Bezug auf Filmbetextungen übertragen wurden und noch werden. Die Stammeinlage des Herrn Willi Böcker wird mit 5000 M bewertet. Die Stammeinlagen der Gesellschafter sind damit erfüllt. Oeffentliche Bekanntmachungen der Gesellschaft erfolgen nur durch den Deutschen Reichsanzeiger.

FTV business goal was to produce and distributor film descriptions and programs and to continue the brand Kino-Bibliothek initiated by Friedrich Carl Rentsch. As mentioned Friedrich Carl Rentsch acted as director of the company. Apart from this there is no evidence of a prior engagement in the film industry by Rentsch.

Willi Böcker on the contrary, partner and chief editor at FTV, had at the same time an identical position at the Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung. This trade journal, rivalling Der Kinematograph and Lichtbild-Bühne, was printed at the printing firm Richard Falk which is associated with the third partner Rudolf Falk. Aside from publishing the trade journal the printer and publisher Richard Falk had other stakes in the film industry as they produced film posters among other printed matter. Known posters are Lebendig tot (1913, FRA), Goldfieber (1913, ITA) and Der Nabob (1913, FRA).9 Aside from film posters Richard Falk printed at least some booklets for releases of Nordische Films Co the German branch of Nordisk Film Co. Some examples are Die Asphaltpflanze, Der Höhen-Weltrekord or Das Recht der Jugend.10

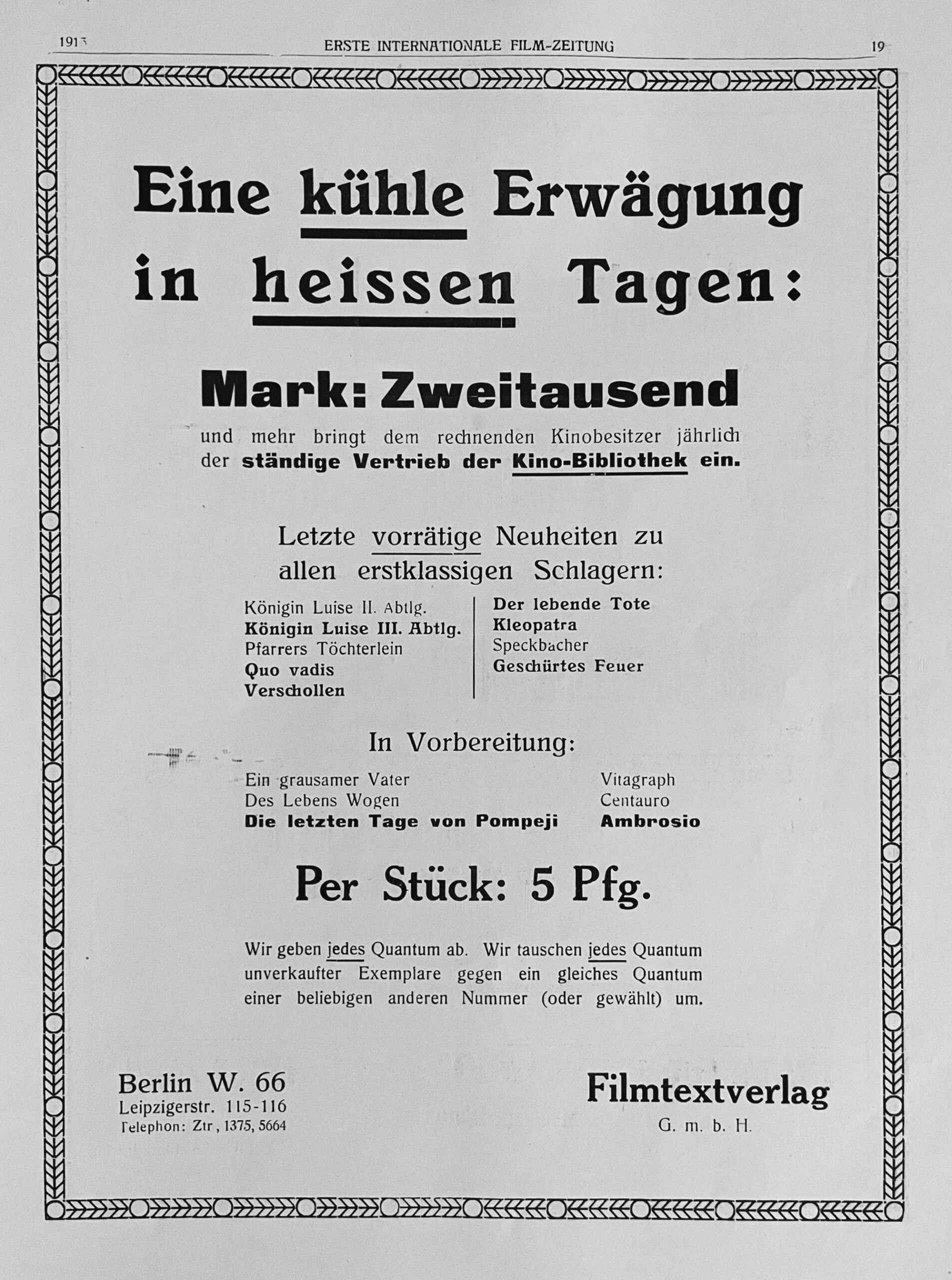

Advertisement in Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung.11

The FTV‘s office was situated in Berlin, initially located at Leipzigerstraße 115-116.12 Shortly after the company relocated to Friedrichstraße 20 in Berlin,13 the same building that the German office of Elge Gaumont used for their business.14

heyday

House advertisement by FTV.15

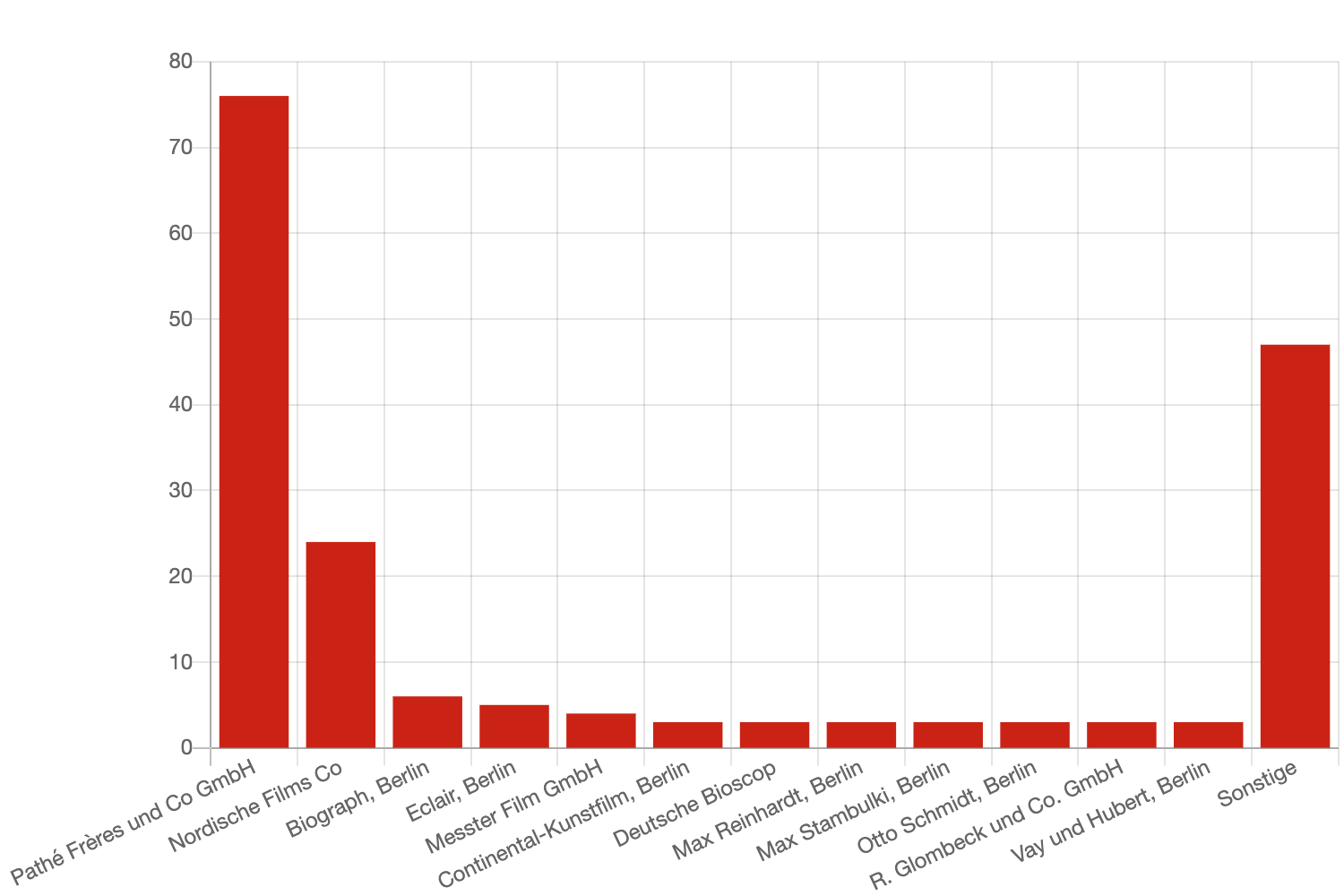

During the year 1913 FTV managed to accompany several releases with booklets. According to an ad in Kinematographische Rundschau they published as many as 200 booklets.16 Out of those 200 titles at least 180 can be verified (see Index of “Kino-Bibliothek” publications). The list includes a broad selection of production companies, featuring American (Selig), Austrian (Jupiter Film, Luna, Wiener Kunstfilm), Danish (Filmfabriken Danmark, Nordisk Film Co), French (Eclair, Eclipse, Gaumont, Lux, Pathé Frères), German (Deutsche Mutoskop und Biograph, Düsseldorfer Film-Manufaktur, Komet Film, Literarischer Lichtbildverlag, Martin Dentler, Messter, Polar Film, Royal Films) and Italian producers (Celio, Cines, Itala, Milano Film, Pasquali, Roma Film, Savoia).

Advertisement by FTV in Kinematographische Rundschau.17

The work of the FTV was accompanied by advertisements, notable in the different German speaking trade journals like Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, Der Kinematograph, Kinematographische Rundschau and Lichtbild-Bühne. Due to the lack of access to Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung it can only be assumed that this trade journal was the major distribution channel by reason of Willi Böckers personal involvement. Yet FTV used the other trade journals more or less frequently for promotional purposes.

the subject

Cover from the booklet Quo vadis? by FTV.18

A booklet like the one accompanying the release of Quo vadis? (Cines-Film, 1913) or The mysterious maiden (Royal Films Düsseldorf, 1913) consisted of 20 pages including the dust jacket. Some booklets weren‘t that extensive, for example the companion to Confetti (Royal Films Düsseldorf, 1913) had only 12 pages in total.

The publication‘s dusk jacket were made from paper with stronger grammage and printed in two colours (orange and black) while the inside was simply black and white. A number of booklets featured house advertising on the inside of the dust jacket. The remaining pages contained a title page, copyright information, the actual film description, sometimes film stills and finally information regarding the producer and distributor of the original film.

The content of the booklet was no reprint of the original script but instead a renarration or synopsis of the film by a writer with allegedly no direct relation to the original producer. This is at least indicated by the correspondence between Nordisk Film Co and their Berlin based branch, who were involved in the production of the booklets that originated from their productions.19 This practice might have worked fine with a film that had no sophisticated storyline but was a rather distorting approach once the film was based upon an original work of art. This was notably the case when FTV tried their approach on the film Atlantis based upon Gerhart Hauptmann‘s novel or Das fremde Mädchen originally based upon Hugo von Hofmannsthal‘s pantomime. After transforming the original work of literature into a script which was transformed into a film it was again transformed into literature – an obviously lossy process. A reason for this proceeding was that the booklet was not directly commissioned during the initial production of the film by the producer itself but subsequently after the release of the film by the FTV instead.

The booklets where initially sold for 5 Pfennig20 to the cinemas and later on sold to visitors for 10 Pfennig or 12 Heller21 through the cinemas or by the publisher directly. Additionally the booklets where sold through the book trade. The booklets could be purchased via subscription directly through the publisher at a price of 2.50 Mark.

Advertisements promised an additional revenue of 2.000 Mark or 2.000 to 3.000 Kronen per year for the cinema owners. This meant selling approximately 40.000 booklets per year, 3.333 per month or 110 a day at a price of 10 Pfennig with a net income of 5 Pfennig per sale. Assuming exemplarily four screenings a day this implies selling 28 booklets per individual screening. If the stated figure falsely implied the transaction volume instead of the revenue there still needed to be sold half of the mentioned numbers. Considering a typical admission starting between 20 to 30 Pfennig22 the printed companions appear to be a rather pricy supplement. The promised revenue appears pretty unrealistic for the situation of an average cinema owner. At least FTV offered to replace unsold quantities with the same amount of other publications at will.23

modus operandi

It is certain that FTV acquired the right to print booklets from several well known film producers. For example the publication for Quo vadis? contains the reference to Cines as well as their German agency. Yet it is uncertain how the process of the acquisition was carried out by FTV and under which terms the agreements were concluded.

In the case of Nordisk Film Co it can be partially reconstructed through business letters. Here the Berlin based German branch Nordische Films Co placed orders for the production of some of FTV‘s publications 24 while initially leaving the headquarter in the dark about the scale of the operation 25. While being baffled at first the Nordisk Film Co encouraged additional publications later on. They even encouraged publications for films that from their point of view were considered minor releases:26

[…]

BESCHREIBUNGEN. Gestern erhielten wir die 60 Abzüge “Die Sphinx”, und erwarten also heute noch, oder spätestens morgen 60 Hefte “Die weisse Dame”. Wir bemerken, dass entweder Hefte oder korrigierte Abzüge “Schatten der Seele” und “Die Mutter” morgen Mittag von Berlin abgehen werden. Wenn korrigierte Abzüge gesandt werden benötigen wir natürlich keine Hefte.

Die Beschreibungen “Das Glück tötet” und “Durch Nacht und Licht” bitten wir baldmöglichst anfertigen und übersenden zu lassen. Auch die kleinen Films dürfen nicht vergessen werden.Hochachtungsvoll

A/S Nordisk Films Co

With the blockbuster Atlantis approaching it‘s release this encouragement apparently turned into eagerness as Nordisk Film Co demanded from their German branch for several days in a row to enable FTV to produce the desired descriptions.27 Finally done the result was deemed insufficient by both Nordisk Film Co and their office in Berlin.28 It is not known how the description turned out but according to Traub and Lavies it was never published.29 Shortly after the release of Atlantis the Nordisk Film Co or their German branch apparently ceased to support FTV‘s efforts as Hoheit Inkognito (FTV booklet no. 186) promoted in January30 was the last known publication featuring a film produced by Nordisk Film Co.

According to the list of publications 24 booklets can be linked with Nordische Films Co and their parent company Nordisk Film Co which translates into approximately 13 % off all publications released by FTV.

Number of publications by FTV per producer or distributor (in case of foreign producers).31

Aside from this example there is another mayor contributor to pool of publications. Over time FTV provided around 70 publications for Pathé Frères in an extensive collaboration. For example Pathé Frères‘ weekly program number 32 featured three longer films – Das fremde Kind, Im Kampf ums Glück and Auf Abwegen – all where made into publications. This pattern continues through the second half of 1913.

beyond one‘s own nose

On May 30th 1913 the Neue Hamburger Zeitung32 printed the following statement regarding Hugo von Hofmannsthals work of literature Das fremde Mädchen referencing an article by Der Kinematograph thereby spreading the information to a wider audience.

Hugo von Hofmannsthal hat einem Berliner Filmtextverlag die kinematographische Verwertung seiner Pantomime Der fremde Vogel überlassen. Grete Wiesenthal hat, wie der Kinematograph berichtet, in der bereits stattgefundenen Aufnahme die Hauptrolle übernommen.

While wrongly referring to another film title – Der fremde Vogel was a film made in 1911 starring Asta Nielsen – this article highlights FTVs aspiration to participate in a significant trend: the emerging production of auteur films in 1913.33

The rights for the film were subsequently bought by Royal-Films,34 a company orchestrated in Düsseldorf by Ludwig Gottschalk and Karl Lohse during the early summer of 1913. The Royal-Films‘ business model was to buy rights to films and to sell them directly to cinemas and smaller distributors. As early as June 1913 DFM instead began to heavily advertise the film.35 The film finally premiered on September 5 of the same year.36 DFM notably highlighted in their advertisements Grete Wiesenthal‘s lead role, her film debut and Hugo von Hofmannsthal‘s creative genius.37 In the end the film received mostly miserable reviews.

Am Schlusse rührte sich keine Hand zum Beifall; schweigend und offenbar peinlich berührt gingen die Zuschauer hinaus.38

An letter39 by Karl Lohse sheds some light on the business relation between FTV and Ludwig Gottschalk‘s company which emphasises the impression that the collaboration between DFM and FTV did not went well after their debut with Das fremde Mädchen. In context of the film Atlantis he points out possible shortcomings when working with FTV and his strong hesitation to accept FTV‘s offer.

Lo/Ba. den 29.September 1913

Titl.

Nordische Film Co.,

KOPENHAGENIn Beantwortung Ihres werten Briefes vom 27. ds. nahm ich davon Kenntnis, das meinerseits keine Abnahmeverpflichtungen für die Broschüren “Atlantis” vom Film-Textverlag vorliegt. Ich werde mir noch reiflich überlegen, ob ich das Geschäft mit dem Film-Textverlag mache, denn es führt immerhin zu allen möglichen Unzuträglichkeiten.

Hochachtungsvoll!

Lohse

Düsseldorfer Film-Manufaktur

Ludwig Gottschalk

One reason for Lohse‘s reluctance might originate in the behaviour shown by FTV. They independently issued a statement in the trade press 40 regarding the origin of the contract with von Hofmannsthal for the film rights.

Der „Filmtextverlag“ G.m.b.H. in Hamburg bittet zwecks Vermeidung von Irrtümern um Klarstellung, dass die Verfilmung der Pantomime „Das fremde Mädchen“ von Hofmannsthal auf einen Vertrag zurückgeht, den der Dichter schon vor Jahr und Tag mit dem Filmtextverlag abschloss und aus welchem die Royal Films Co., G.m.b.H. das Filmrecht gewann.

FTV published a clarification with the goal to avoid factual errors stating that the picturisation of the film could the traced back to an original contract with the FTV that the poet agreed to. Based on that contract the rights to produce the film were granted to the Royal-Films by the FTV. The necessity to emphasise the importance of their own role in the process of the production of the film highlights the apparent discontent by FTV with way the advertisement for the film was handled by DFM. Something one would not do in a healthy business relationship.

anticlimax

Demise comes in various flavours but FTV‘s is ambiguous. What is definite is that both Willi Böcker and Rudolf Falk served in the Great War. While Willi Böcker was conscripted in August 1914 Rudolf Falk enlisted voluntarily around the same time.41 With two of the three founders absent FTV‘s fate must have laid solely in the hands of Friedrich Carl Rentsch. Apart from that information is scarce. According to Traub and Lavies FTV produced publications between 1913 and 1914 42 indicating that eventually the production of publications was indefinitely adjourned in 1914.

When identifying the release dates for the films it becomes obvious that the productions must have stopped long before the start of the Great War as the last known film used for a booklet was released in January 1914.43 Nevertheless promotional activities kept on as long as August of the same year.44

bottom line

To profit additionally from cinemagoers it was common practice in 1912 for cinemas in Germany to sell give-aways as a memento to accompany the viewing experience. Give-aways like publications with a synopsis of the film were a common addition to the producer‘s and distributor‘s offerings. The idea to produce publications as an independent publisher was what made FTV‘s approach unique. Within a year the company accomplished to release as many as 200 publications for various films. FTV managed to produce publications for almost all major producers and distributors of films in Germany. Yet the company‘s decline was more rapid than its ascent. Production seems to have dropped almost instantly as no further publications can be traced past the first quarter of 1914.

For a long time FTV‘s approach remained unrivalled. It took 11 years for a conceptual successor. By 1925 the Lichtbild-Bühne produced a series of publications under the identical name Kino-Bibliothek.45 This time it was far less successful as only 13 different titles were produced until the series was discontinued.

Updates

- December 20, 2023; minor corrections.

- December 11, 2023; initial version.

related Material

Index of “Kino-Bibliothek” publications

copyright

The images used in this article are taken from:

- ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (notes on usage).

- Internet Archive.

Note the individual footnotes for details. If not specified reproductions where made by myself.

accessibility of sources

The majority of the film trade journals is either available at Internet Archive (Der Kinematograph, Lichtbild-Bühne) or ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Kinematographische Rundschau).

Newspapers can be accessed via zeit.punkt NRW (Kölnische Zeitung) or Europeana (Neue Hamburger Zeitung).

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, 11. July 1914, no. 28, page 85 ↩︎

-

Lichtbild-Bühne, no. 14, 6. April 1912, page 49 ↩︎

-

From left to right: Velberter Zeitung, no. 42, 18. February 1911, page 4; Die Fackel, no. 29, 22. July 1911, page 1; Dürener Zeitung, no. 5, 8. January 1912, page 4 ↩︎

-

Hagener Zeitung, 4. April 1911, no. 82, page 4; “Textbücher á 5 ₰ an der Kasse erhältlich.“ ↩︎

-

Compare for example Programm des Edison-Theaters featuring Der schwarze Traum; https://video.dfi.dk/filmdatabasen/19842/den-sorte-droem_program_©dfi.pdf ↩︎

-

Ohligser Anzeiger, no. 296, 17. Dezember 1912, page 3; available at zeitpunkt.nrw ↩︎

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 31, 1. August 1914, page 82 ↩︎

-

For example: Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, no. 38, 14. February 1913, page 27 ↩︎

-

Stach, Babett; Morsbach, Helmut (1992): German film posters : 1895 – 1945. Saur, München, 1992. ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF IX 40 ↩︎

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 18, 3. May 1913, page 19 ↩︎

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 18, 3. May 1913, page 19 ↩︎

-

Der Kinematograph, no. 322, 26. February 1913 ↩︎

-

Der Kinematograph, no. 52, 25. December 1907 ↩︎

-

Röder, Helene (1913). Confetti. Filmtext-Verlag, Berlin. ↩︎

-

Kinematographische Rundschau, no. 307, 25. January 1914, page 101 ↩︎

-

Kinematographische Rundschau, no. 307, 25. January 1914, page 101 ↩︎

-

Felsner, Harry (1913). Quo vadis?. Filmtext-Verlag, Berlin. ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF 690, 11/17/1913 Blatt II. ↩︎

-

advertisement in Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 18, 3. May 1913, page 19 ↩︎

-

Röder, Helene (1913). Confetti. Filmtext-Verlag, Berlin. ↩︎

-

Müller, Corinna (1994). Frühe deutsche Kinematographie. Formale, wirtschaftliche und kulturelle Entwicklungen 1907 – 1912. J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar, 1994. ↩︎

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 18, 3. May 1913, page 19 ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 264, 10/17/1913, Blatt III: “Mit Ihren Bestellungen von Beschreibungen von Filmtextverlag gehen wir konform.” ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 413 + 414, 10/29/1913, Blatt I: “Wir verstehen deshalb nicht, wie es kommt, dass der F.T.V: diese Beschreibungen für uns angefertigt haben, und erwarten hierüber gern Ihre Aufklärung.” ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 590, 11/11/1913, Blatt II: “Auch die kleinen Films dürfen nicht vergessen werden.” ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 667, 11/15/1913, Blatt I: “Sobald der “ATLANTIS”-Film censiert ist, müssen Sie den Film für den Film-Textverlag zeigen, und den Verlag bitten die Beschreibung absolut express zu besorgen.”; Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 690, 11/17/1913, Blatt II: “Auch sollen Sie bitte nicht vergessen den Film nach der Zensierung dem Filmtextverlag zeigen zu lassen, damit de die Beschreibung schleunigst angefertigt wird.”; Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 844, 11/26/1913, Blatt 2: “Wir ersuchen heute Herrn Gottschalk Ihnen eine in seinem Besitz befindliche ältere Probekopie zu übersenden, die mit der zensierten identisch, nur ziemlich abgenutzt ist. Diese können Sie zur Vorführung für den F.T.V. und für evtl. andere … verwenden.” ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF II 28, kopi-bøger, 958, 12/01/1913, Blatt IV: “BESCHREIBUNG “ATLANTIS” Wir sind mit Ihnen einig, dass die Beschreibung es F.T.V. nicht gut ist. Teils ist sie viel zu lang teils enthält sie viele Unrichtigkeiten, die also hoffentlich in der neuen Fassung, die wir am Mittwoch erwarten vermieden sind.” ↩︎

-

Traub, Hans / Lavies, Hanns Wilhelm. 1940. Das deutsche Filmschrifttum. Leipzig: Verlag Karl W. Hiersemann, p. 186f ↩︎

-

Der Kinematograph, no. 367, 7. January 1914 ↩︎

-

based on Index of “Kino-Bibliothek” publications ↩︎

-

Neue Hamburger Zeitung, no. 247, 30. May 1913, page 7 ↩︎

-

For a contemporary classification: “Der Autorenfilm und seine Bewertung”, in: Der Kinematograph, no. 326, 26. March 1913 ↩︎

-

Der Kinematograph, no. 343, 23. July 1913; “Der „Filmtextverlag“ G.m.b.H in Hamburg bittet zwecks Vermeldung von Irrtümern um Klarstellung, dass die Verfilmung der Pantomime „Das fremde Mädchen” von Hofmannsthal auf einen Vertrag zurückgeht, den der Dichter schon vor Jahr und Tag mit dem Filmtextverlag abgeschlossen und aus welchem die Royal Films Co., G.m.b.H., das Filmrecht gewann.“ ↩︎

-

Der Kinematograph No. 338, 18. June 1913 ↩︎

-

Lichtbild-Bühne, No. 37, 13. September 1913, page 51 ↩︎

-

For example see Der Kinematograph, No. 337. 11. June 1913; Wiesenthal is idealised as “Die größte aller Tänzerinnen” and von Hofmannsthal as “Der bedeutendste aller Autoren” ↩︎

-

Kölnische Zeitung, no 1014, 8. September 1913, page 1 ↩︎

-

Det Danske Filminstitut (DFI), NF XII, 88:14 ↩︎

-

Der Kinematograph, no. 343, 23. July 1913 ↩︎

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 33, 15. August 1914, page 5 ↩︎

-

Traub, Hans / Lavies, Hanns Wilhelm. 1940. Das deutsche Filmschrifttum. Leipzig: Verlag Karl W. Hiersemann, p. 186f referenced in Lange, Jasmin. 2010. Der deutsche Buchhandel und der Siegeszug der Kinematographie 1895–1933. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, page 135 ↩︎

-

Booklet no. 186 Hoheit Inkognito by Nordisk Film Co ↩︎

-

Erste Internationale Film-Zeitung, no. 31, 1. August 1914, page 82 ↩︎

-

Traub, Hans / Lavies, Hanns Wilhelm. 1940. Das deutsche Filmschrifttum. Leipzig: Verlag Karl W. Hiersemann, p. 187 ↩︎

Leave a Reply